Last year Labor announced that if elected it would refer health funding, particularly private health insurance, to the Productivity Commission, it being 50 years since the value of PHI was last examined by government. It appears, however, that Labor is squibbing on its promise to subject PHI to economic scrutiny, abandoning its historical commitment to defend Medicare from being undermined by PHI.

One of the most vehement political struggles of the last seventy years has been over health policy, in particular the question whether health insurance should be funded by a single tax-funded national payer, such as Britain’s NHS, or by individuals’ contributions to private health insurance (PHI).

In the years following the Pacific War the Chifley Labor Government planned to establish a government scheme similar to the NHS, but strident opposition from health insurers and the British Medical Association, the organisation representing Australian doctors (who hadn’t quite gotten used to the idea of federation), thwarted their plans. The Menzies Government, elected in 1949, maintained its support for PHI, mainly through providing tax deductions for PHI fees, which meant the higher one’s income the cheaper was PHI, because the income tax scales were highly progressive.

It was not until 1972, when Labor regained office, that it had another chance to reform health funding, with its plan for Medibank, the forerunner of Medicare (not to be confused with the private health insurer with the same name). Again, there was a struggle, because the Coalition-controlled Senate blocked legislation to establish Medibank. But so determined was Labor to introduce Medibank that just 18 months after being elected it went to the extent of calling and winning a double-dissolution election, with Medibank as the prime issue.

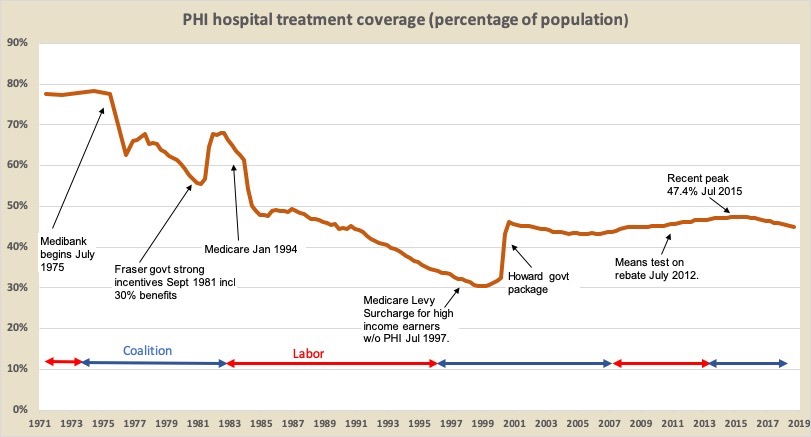

With Medibank in place, PHI coverage rapidly fell from around 80 per cent to 60 percent of the population. Then the Fraser Coalition Government, elected in 1975, restored support for PHI, and in 1981 it introduced a number of incentives virtually making PHI compulsory, thus pushing up PHI coverage up once more.

These and subsequent movements are shown in the graph below. The general story of health funding has been the Coalition’s commitment to support PHI, while Labor has invested its political energy into Medicare.

It was no surprise that the Hawke Labor Government, elected in 1983, resurrected Medibank under the name Medicare. PHI coverage immediately fell to 50 per cent, and over the next 13 years while Labor was in office if slowly fell to 30 percent.

True to ideological form, however, the Howard Coalition Government introduced a huge swag of incentives for PHI, initially a surcharge on high income earners without PHI, and then a rebate (initially of 30 percent), a massive advertising campaign (conveying the impression that without PHI one would have no cover), and a set of incentives to get people enrolled in PHI by the age of 30 so they could subsidise older members.

PHI membership shot up, and it peaked again at just over 47 per cent in 2015, but since then, in spite of ever-increasing budgetary assistance (now around $11 billion annually including $5 billion cash outlays and $6 billion revenue forgone in tax expenditures), membership numbers have stagnated at just over 11 million, which means that as population rises, coverage has now slipped back to 45 per cent. Of even more concern to the funds is that since 2015 they have lost 250 000 members aged under 55, while gaining almost the same number of members over 55. They’re losing profitable members.

In short, people are finding that PHI does not offer value-for-money. The price of PHI has been consistently rising two to three percent ahead of inflation. People often have poor claims experience, and over time learn that they are well-served by the public hospital system.

From their personal experiences consumers are learning what economists have known for a long time. PHI is an expensive and inequitable way to fund health care, and it does nothing that a tax-funded single national insurer such as Medicare doesn’t do better. Because PHI has become the prime funding mechanism for private hospitals it has blocked opportunities for competition between private and public hospitals. Because it lacks the cost control discipline that governments apply to public hospitals, it has contributed to a general escalation in health care costs and has attracted resources, particularly medical specialists, away from public hospitals. Far from relieving stress on public hospitals it has worsened them. (A full analysis of the inefficiency and waste in PHI is provided in a paper John Menadue and I prepared for the Centre for Policy Development in 2012.)

PHI has enjoyed a privileged life, particularly from Coalition governments. To quote Tony Abbott, support for PHI “is an article of faith for the Coalition. Private health insurance is in our DNA.” So much for evidence-based-policy or cost-benefit-analysis.

This year marks 50 years since PHI was last subject to economic scrutiny when in 1969 the government-commissioned Report of the Committee of Enquiry into Health Insurance (the “Nimmo Report”) found PHI to be wasteful, inefficient and inequitable. Its findings helped the Whitlam Government shape Medibank.

Over the subsequent half-century every other significant industry receiving public subsidies has been subject to scrutiny – everything from car manufacturing through to taxis – but not PHI. In 1996 the Howard Government sent a reference to the Productivity Commission, but that was a loaded reference about how PHI should be supported, rather than about whether it should be supported. More recently, following intense lobbying from insurers, the Rudd Government’s Health and Hospital Reform Commission exempted it from scrutiny. And even more recently it has been the only part of the finance sector not scrutinised by the Royal Commission into the finance sector.

Therefore it was a welcome announcement last year that Labor, if elected, would be sending a reference on PHI to the Productivity Commission. Here would be an opportunity to subject it to the scrutiny that Justice Hayne has applied to other financial intermediaries. Just as mortgage brokers and financial advisers have been unable to demonstrate how their fees have been justified in terms of adding value, so too would health insurers find it difficult to demonstrate how their massive and growing subsidies have done anything for Australians’ health care that the Australian Taxation Office and Medicare could not do better.

But it seems that Labor, rather than seeing the decline of PHI membership as the slow demise of a high-cost and inefficient industry, is seeing it as a problem. Its consultation document on the proposed Productivity Commission reference reads as if retaining and even strengthening PHI is beyond question (without providing any defence of this view), and it assumes that private hospitals and specialists will continue to rely primarily on PHI rather than being brought into the same funding pool as public hospitals.

The Party’s starting point, outlined in that paper, is that private insurance will “continue to play a key role” in funding health care. It reads like a cut-and-paste of the Howard Government’s reference on how to save PHI, even though the Commission’s final report on that occasion expressed clear dissatisfaction with its limited terms of reference, and recommended that there be “a broad public inquiry into Australia’s health system”.

Here should be an opportunity to do something that hasn’t been done for fifty years, with a simple reference embodying Labor’s social-democratic principles. My suggestion for such a reference is that the Commission should be asked:

to examine and recommend on health care funding, having regard to principles that scarce resources should be allocated on the basis of therapeutic need, rather than income, wealth or privileged access to third party sources, and that individuals’ income or wealth should not impede access to health care.

Other readers of Pearls and Irritations may have different advice for Labor. If so they can read the consultation document (it’s only 17 pages) and at the end they will find directions on making a submission. I suggest not following their leading “questions for discussion”, which all read as if they have been written by advocates for PHI.

Ian McAuley is a retired lecturer at the University of Canberra and a fellow of the Centre for Policy Development.