It was always going to be a tough ask. How to remove all that stimulus, all those trillions of freshly minted dollars in emergency money from an economy, without causing conniptions on financial markets?

The shake-out on global stock markets is long overdue.

Despite an economy struggling to raise itself off the mat, American investors pushed Wall Street to record levels in 2013 and then doggedly higher, thanks to radical steps by the US Federal Reserve.

Not only did it cut interest rates to zero, to ward off the worst effects of the global financial crisis, it engaged in three long bouts of money printing, pumping more than $US3 trillion into the financial system.

Europe and Japan followed suit while China embarked on a debt spree of unrivalled proportions.

Much of that extra cash, around $US20 trillion, flooded into stock and bond markets, inflating values and distorting returns.

Along the way, investors threw aside every traditional measure of value.

Until last week, Wall Street was collectively valued at more than 25 times earnings. Normally it is around 15 to 16.

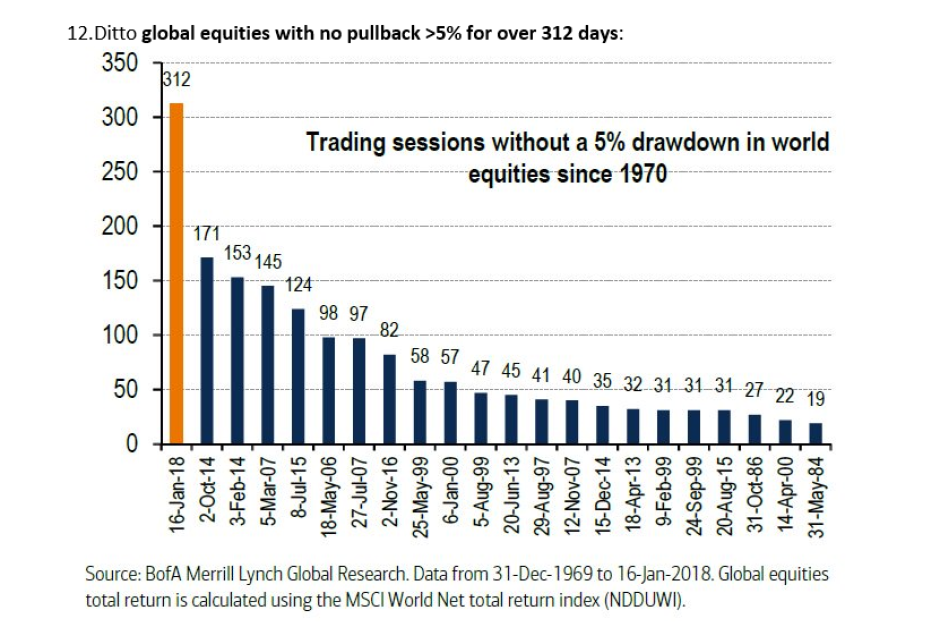

It had gone for an unprecedented 312-day run without a 5 per cent pullback. Normally, there are three a year.

The party had to come to an end at some stage, and it appears that happened last week.

The spectre of rising interest rates has been hovering above Wall Street and global markets for months, even as investors pushed the Dow Jones Industrial Average forever higher.

Federal Reserve chairman Janet Yellen let slip at her final outing last week that, with the American economic recovery gathering pace, rates may rise a little quicker than expected.

On Friday, the good news finally arrived. Not only were US jobs figures better than expected, but wages were growing.

That sent shivers through the market as it finally dawned on punters that the era of emergency interest rates was rapidly coming to an end.

High risk stocks, many of them hugely overvalued, were ripe for a fall.

How will this affect us?

Unlike Wall Street, which until last week sat about 88 per cent higher than its 2007 peak, our market has never managed to even get close to breaching record levels.

As of today, we still remain about 12 per cent below our 2007 peak.

Unlike Wall Street’s lofty valuations, companies listed on the Australian Securities Exchange are trading at about 16 times earnings, not far off long-term averages.

Partly that’s because Australia never jumped on board the money printing train.

And while we blissfully chugged through the worst of the global financial meltdown a decade ago, our economy since has run out of puff.

What spare cash Australians did scrape together when the Reserve Bank slashed interest rates to record levels, we plunged into real estate.

But that doesn’t mean we won’t feel the impact.

As a major trading nation, exporting food and raw materials to the rest of the world, we are hugely exposed to any change in the global economic momentum.

Any major downturn on global markets affect Australia, as we’ve witnessed in recent days.

Not only that, our superannuation funds over the years have poured almost half the $2.5 trillion they have under management into Australian stocks.

A large chunk of the remainder is invested on global markets, with Wall Street and Europe accounting for most.

Why do market movements matter anyway?

Stock markets tend to grind higher, sometimes for years on end, before suddenly falling in a heap.

That’s because they are driven by two competing forces: greed and fear.

Economists assume that individuals always act rationally, that we always act in our own best interests. There’s an element of truth to that.

But they forget about that great wildcard in the human condition: emotion.

Never is that more apparent when it comes to money.

As soon as a market in almost anything starts rising — from tulips to stocks and even an arcane and mysterious concept like Bitcoin — we all want a slice of the action, even if we have little or no understanding of it.

Then, when values start to decline, everyone decides to get out, pretty much at the same time.

If enough people are burnt, and end up nursing losses, that makes them poorer which means they spend less.

That’s when governments and the Reserve Bank become concerned.

Less spending means lower profits and, if it continues, job losses.

That’s the reason why central banks from Washington to London and Beijing to Tokyo went overboard with economic stimulus a decade ago during the crisis.

In doing so, however, they merely laid the ground for the next crisis.

What’s likely to happen now?

A healthy and much needed correction? Or the start of a major crash?

They are the questions on everyone’s lips.

No-one knows the answer.

Wall Street has risen 40 per cent since Donald Trump was elected President, and gone an unprecedented 312 trading days without a significant pullback based primarily on the misplaced assumption that his low taxing, big spending plans would stimulate growth.

While they certainly would boost growth, they may also fuel a big rise in inflation just as wages are starting to take off. That could prompt the new US Federal Reserve chairman Jerome Powell to push rates higher at a much quicker pace than previously thought. And that would be a big wake-up call to Wall Street.

What happens next depends on central banks. If Mr Powell, a Trump appointee, decides to hold back on rate rises, in order to protect market investors and keep his boss happy, he may merely be delaying the inevitable.

If the global economy is ever to make a full recovery and allow interest rates to return to normal, the frothy markets they have created have to readjust, painful as that will be.

Ian Verrender is the business editor of the ABC

This article appeared yesterday on the ABC website.