Providing housing finance has always been a major part of banks’ business. But how did we allow them to make housing into speculators’ playthings?

Remember Rob Stich’s 1997 movie The Castle? The family patriarch Kerrigan, a tow-truck driver and DIY improver of his own modest house, is confronted by a developer trying to use compulsory acquisition powers to buy his property. He takes the case to the High Court and wins.

In large part it’s about the injustice of European settlers in Australia seizing land from its original owners. But it’s also about how the Kerrigan family valued their house, “a home built with love and shared memories”. It simply wasn’t for sale.

We might also remember the 2017 Four Corners program Betting on the House, including the case of Roy and Rowena, a young couple with average incomes, who had 7 investment properties, on their way to owning 20 properties, using rising market values on their existing portfolio as collateral. The returns they expected were so lucrative that they didn’t even own the apartment they lived in.

These two cases – one fictional with a happy ending, the other real with an unrevealed but almost certainly unhappy ending – reveal two radically different views of how people value housing. To put it into the language of economic philosophers, while the Kerrigan family value their house in terms of their enjoyment (“value in use”), Roy and Rowena see housing as currency with the same attachment as one may have to a bank bond or a wad of $50 notes (“value in exchange”).

While Justice Hayne’s report on the finance sector was critical of the less-than-rigorous ways in which banks assessed borrowers’ capacity to repay housing loans, he didn’t comment on the way the finance sector has had a stake in seeing housing become a commodity of financial speculation – what Geraldine Doogue, in an interview about the Royal Commission, referred to as “the financialisation of housing”.

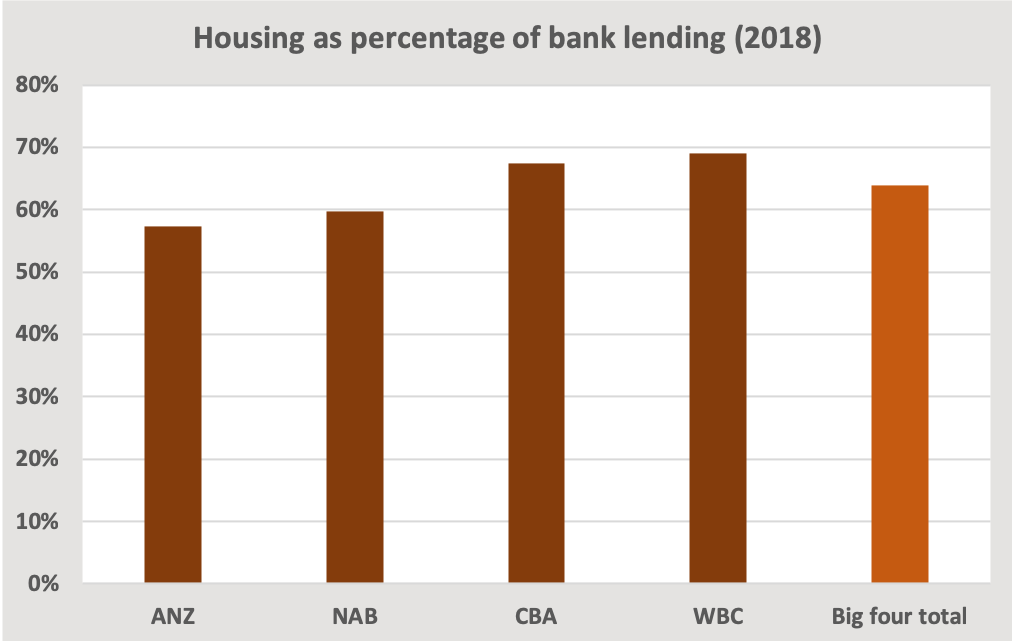

Our banks are heavily involved in housing. Their main business has been in transactional banking and in providing housing finance: almost two thirds of the big four banks’ loans are for housing. But while mortgages for owner-occupiers provide steady background business, they don’t offer much prospect for growth. Looking at the age of Kerrigan’s house, and considering all the years it would have taken to cobble together those additions and extensions, we can guess that he’s probably paid off his mortgage, and that he has no intention to upgrade to a new house and to take on a new mortgage.

Our banks are heavily involved in housing. Their main business has been in transactional banking and in providing housing finance: almost two thirds of the big four banks’ loans are for housing. But while mortgages for owner-occupiers provide steady background business, they don’t offer much prospect for growth. Looking at the age of Kerrigan’s house, and considering all the years it would have taken to cobble together those additions and extensions, we can guess that he’s probably paid off his mortgage, and that he has no intention to upgrade to a new house and to take on a new mortgage.

By contrast Roy and Rowena, on the front line of financial dynamism, are attractive customers. Banks, and hangers-on in the finance sector including mortgage brokers and real-estate agents, all do well out of housing turnover.

Perhaps (probably) Roy and Rowena will become over-committed and the bank will have to foreclose and take a loss on their mortgages, but that’s collateral damage, covered, the bank trusts, in its provision for bad and doubtful debts.

To the banks such losses are simply a cost of doing business. If a bank were to find that none of its borrowers ever defaulted it would probably be judged to be too conservative in its risk-management – in the same way as an investor with a portfolio of shares would expect some losses. In fact, in an article buried in the financial pages last Wednesday, ANZ Bank chief executive Shayne Elliott suggested that his bank may have been “overly conservative” in its loans for owner-occupiers, and was taking steps “to increase volumes in the investor space”. That’s financespeak for seeking out more speculators like Roy and Rowena.

To a bank a default is merely an accounting entry. To those affected, particularly if their own home is involved, a foreclosure is a tragedy. It happens not only to those who were carried away by the housing bubble – an irrational enthusiasm irresponsibly hyped up by the Coalition Government’s policies on negative gearing and capital gains tax – but also to those who have used their homes as collateral for small business investment. There are many others who haven’t suffered from repossession or personal bankruptcy, but who have been hurt by the housing bubble. They including hopeful first home buyers locked out of the market and those who bought in near the top of the market. Even a falling market is less beneficial to first-home buyers than one may think, according to analysis by Chris Leisham of the University of Adelaide.

No doubt if the commission had been given broader terms of reference, it would have identified the housing bubble as a problem brought on by the interaction of bad policy and the financial sector’s incentives to chase turnover. But the problem goes beyond housing or even the finance sector. It’s about the way we have allowed the rules of the market to dominate our lives.

The distinction between value in use and value in exchange goes back to the writings of Aristotle, Aquinas and Marx. They all argued that there are transactions that should not be determined solely by the rules that emerge in markets (the workings of Smith’s “invisible hand” as they were later to be called). Markets had their defined place, often bounded in place (the market square, or the retail zone in more recent times) and in time (market days, or specified shopping hours).

In 1944 the Austro-Hungarian political philosopher Karl Polanyi, in his book The Great Transformation, prophetically warned about the emergence of the “market society”. Echoing those earlier philosophers, he argued that from time immemorial, markets had operated, but they had been subservient to society’s norms of behaviour. He believed, correctly, that the postwar era would see the expansion of the market into all aspects of life. He was particularly critical of the idea of a “labour market” and a wage set by the market interaction of supply and demand, because “labour” (i.e. people), unlike cars, carrots or clothes, is not a commodity brought into existence with the purpose of being traded on a market.

He would have been critical of the way in our current age politicians talk about tradeoffs and choices between social policies and economic policies, because an economic policy that does not contribute to social outcomes – people’s wellbeing – is meaningless. A manifestation of that confusion is a belief, revealed by opinion pollsters, that Labor is stronger on social policy while the Coalition is stronger on economic policy, as if “the economy” is some god that must be appeased with human sacrifice if necessary.

In the 75 years since Polanyi wrote The Great Transformation there has been a huge expansion of the market. While in his days there were newspapers and radio, their intrusion into the hitherto private space of our homes was minor compared with the later intrusion of television and on-screen advertising on websites. Public spaces have also been taken, over not only by billboards but also by cellphone apps that can alert us to the presence of the nearest coffee shop. Shopping and banking hours have become deregulated in our 24/7 market. Housing has not bene exempt from this movement. And the market has expanded its scope in education, child care, health care, and utilities.

People have always bought and sold houses as they move and trade up or down, and there have always been investors who have bought real-estate as long-term capital-stable assets, with net rental income, rather than short-term capital gain, as their dividend. But in recent years, particularly since small investors moved away from equities following the 2008 financial crisis, speculation in housing has become more widespread. It is notable, for example, that property portals The Domain and the REA Group have been considered the most profitable parts of the media business.

Polanyi’s message is repeated today by political and economic philosophers such as Harvard’s Michael Sandel (What Money Can’t Buy: The Moral Limits of Markets) and Mariana Mazzucato (The Value of Everything: Making and Taking in the Global Economy). Surveying the damage inflicted by unfettered markets, they challenge us to consider how to bring markets back where they belong – subject to society’s norms and moral principles.

If we consider that question we may not opt for a reversion to days gone by – pubs closing at six o’clock, mandated retail price maintenance – but we would surely want to rein in the market when it comes to our basic need for shelter and a physical place in the community.

Ian McAuley is a retired lecturer at the University of Canberra and a fellow of the Centre for Policy Development.